When we publish a scientific research article, we post a summary of the article below. Each of the articles has been reviewed by other researchers. You can view the full published articles by clicking on the link for each article. Most scientific journals charge for viewing articles, but we’ve also linked to pre-prints (unformatted versions of the published articles), or you can contact us, and we can provide you with a version.

We are committed to using affirming language that reflects the wishes of the disability community. We acknowledge that language is constantly evolving and are committed to being part of that conversation. Currently, we are following the suggestions outlined by Bottma-Beutel and colleagues (2021) for avoiding ableist language and the guidance of our research advisory board. Older articles may use uncomfortable language for some readers–even articles that seem relatively recent, as they may have been written years before publication. We apologize for any distress this causes.

Sex.Ed.Agram: Co-created Inclusive Sex Education on Instagram

Curtiss, S.L., Myers, K., D’Avella, M., Garner, S., Kelly, C., Stoffers, M., & Durante, S. (2023). Sex.Ed.Agram: Co-created inclusive sex education on Instagram. Sexuality and Disability, Online first, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-023-09794-y

A preprint of the whole article is free, and the summary is below.

Service Models for Providing Sex Education to Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities in the United States

Curtiss, S.L. & Stoffers, M. (2023). Service models for providing sex education to individuals with intellectual disabilities in the United States. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, Online first, https://doi.org/10.1177/17446295231164662

A preprint of the whole article is free, and the summary is below.

Cultural Humility in Youth Work: A Duoethnography on Anti-racist, Anti-ableist Practice

Curtiss, S.L. & Perry, S.C. (2023). Cultural humility in youth work: A duoethnography on anti-racist, anti-ableist practice. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, Online first, https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2023.2178756

Contact us to access this article, or check out the summary below.

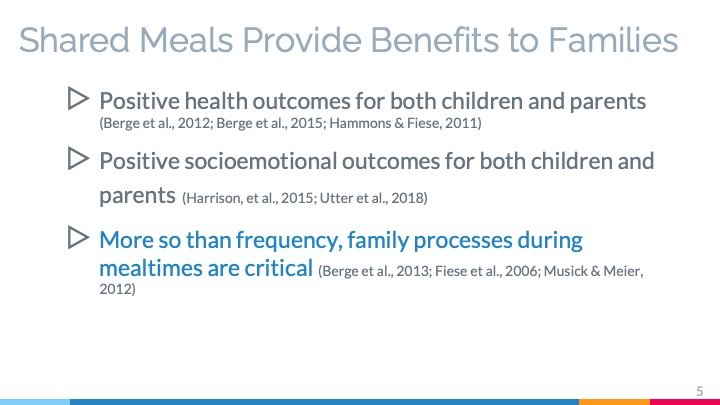

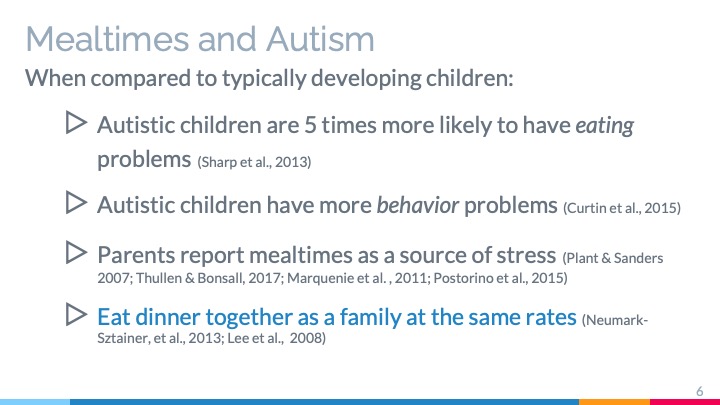

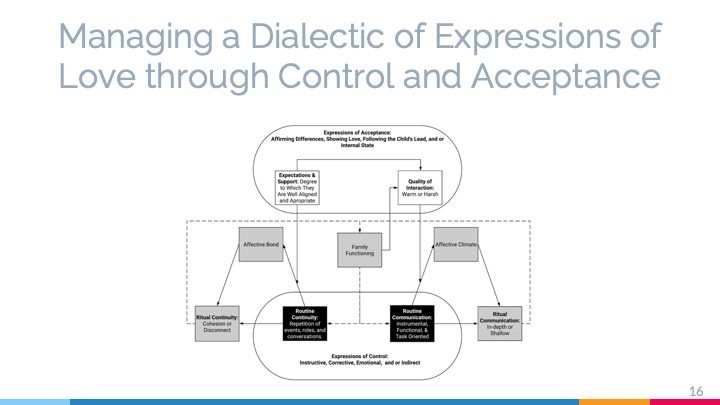

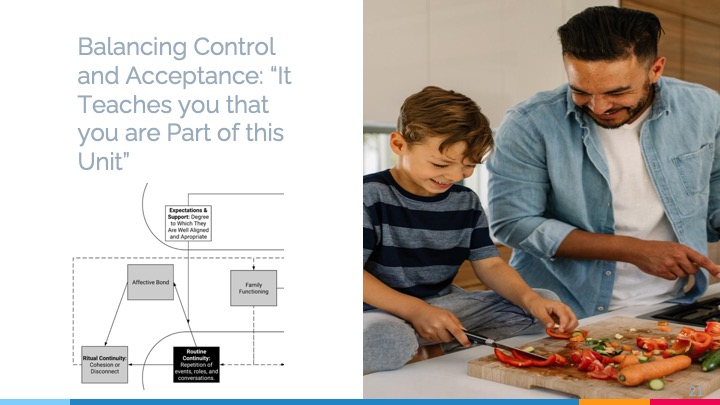

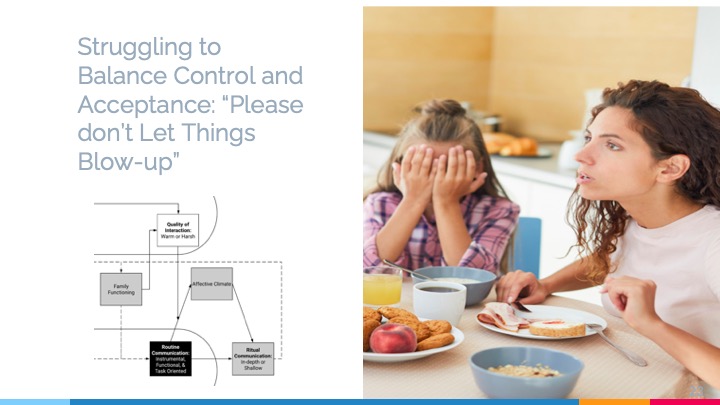

A Dialectic of Control and Acceptance: Mealtimes with Children on the Autism Spectrum

Curtiss, S.L. & Ebata, A. (2021). A dialectic of control and acceptance: Mealtimes with children on the autism spectrum. Appetite, Online first. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105327

A preprint of the whole article is for free, and the summary is below.

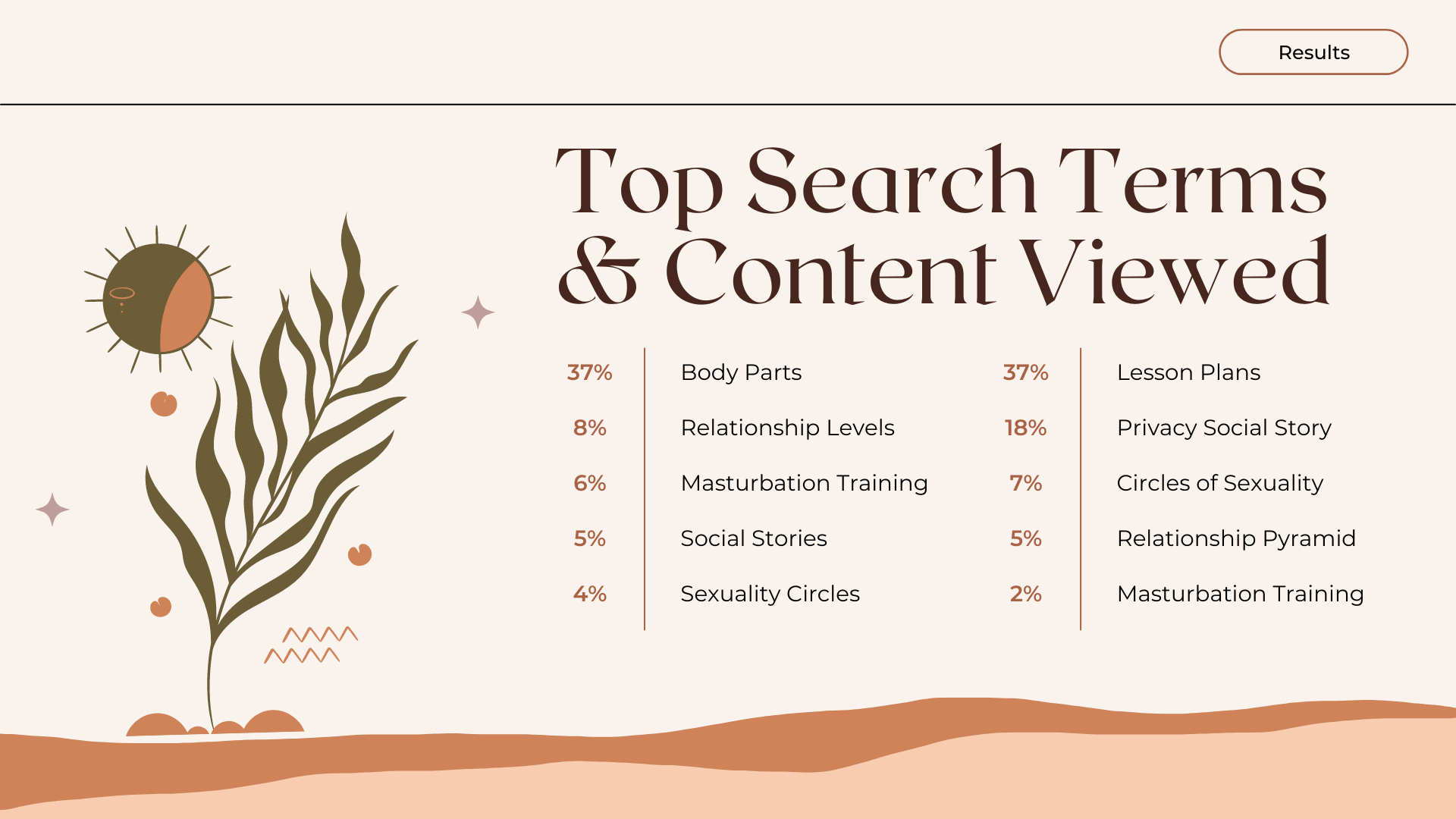

Disseminating Resources Online for Teaching Sex Education to People with Developmental Disabilities

Curtiss, S.L. & Stoffers, M. (2021). The birds and the bees: Disseminating resources online for teaching sex education to people with developmental disabilities. Sexuality and Disability, Online first. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-021-09703-1

A preprint of the whole article is free, and the summary is below.

Autistic Young Adults’, Parents’, and Practitioners’ Expectations of the Transition to Adulthood

Curtiss SL, Lee GK, Chun J, Lee H, Kuo HJ, & Ami-Narh D. (2020). Autistic Young Adults’, Parents’, and Practitioners’ Expectations of the Transition to Adulthood. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, Online First. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165143420967662

A preprint of the whole article is free, and the summary is below.

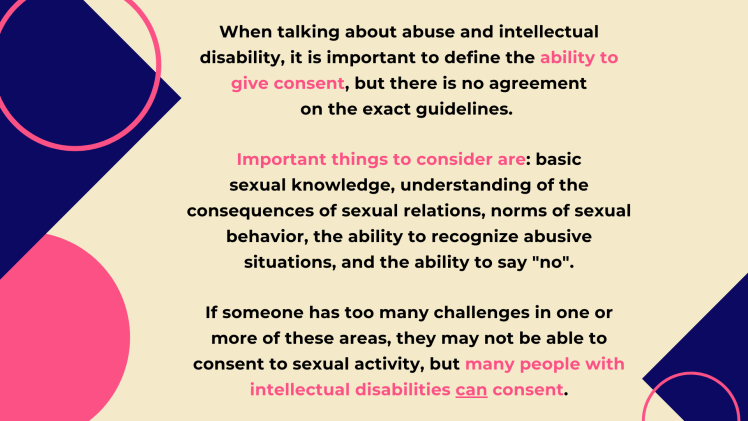

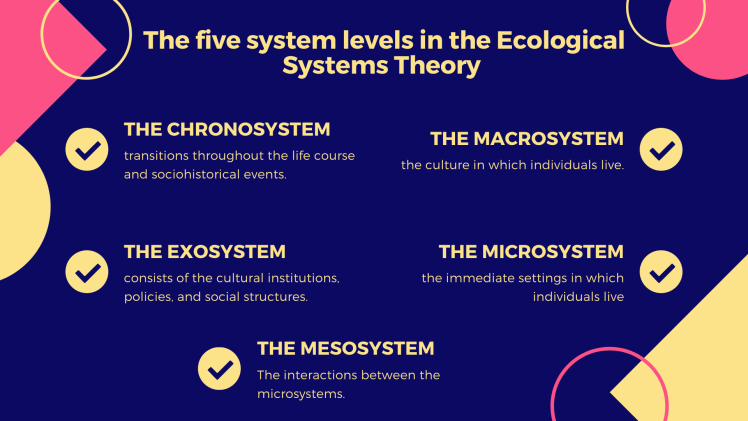

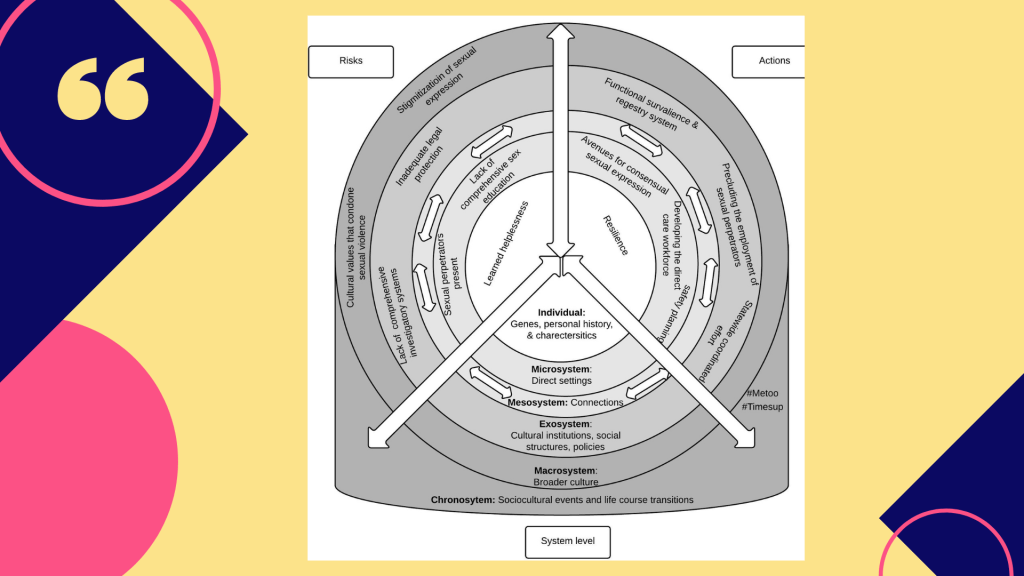

Understanding the Risk of Sexual Abuse for Adults with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities from an Ecological Framework

Curtiss, S. L., & Kammes, R. (2020). Understanding the Risk of Sexual Abuse for Adults With Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities from an Ecological Framework. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 17(1), 13-20. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12318

A preprint of the whole article is free, and the summary is below.

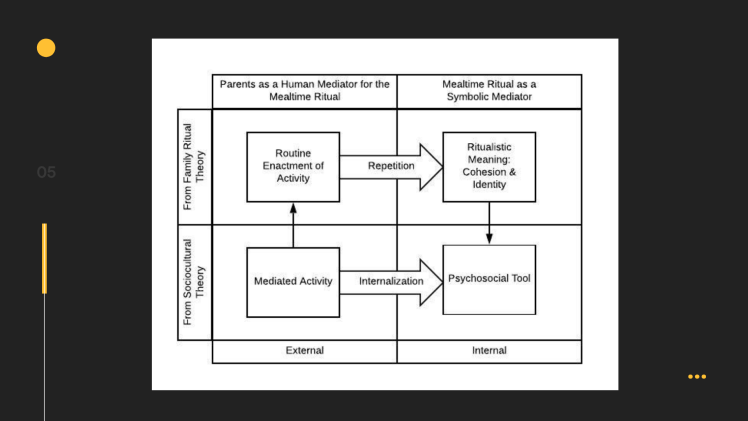

Integrating Family Ritual and Sociocultural Theories as a Framework for Understanding Mealtimes of Families With Children on the Autism Spectrum

Curtiss, S. L. (2018). Integrating family ritual and sociocultural theories as a framework for understanding mealtimes of families with children on the autism spectrum. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 10(4), 749-764. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12298

A preprint of the whole article is free, and the summary is below.

The Nature of Family Meals: A New Vision of Families of Children with Autism

Curtiss, S.L. & Ebata, A.T. (2019). The nature of family meals: A new vision of families of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(2), 441-452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3720-9

A preprint of the whole article is free, and the summary is below.

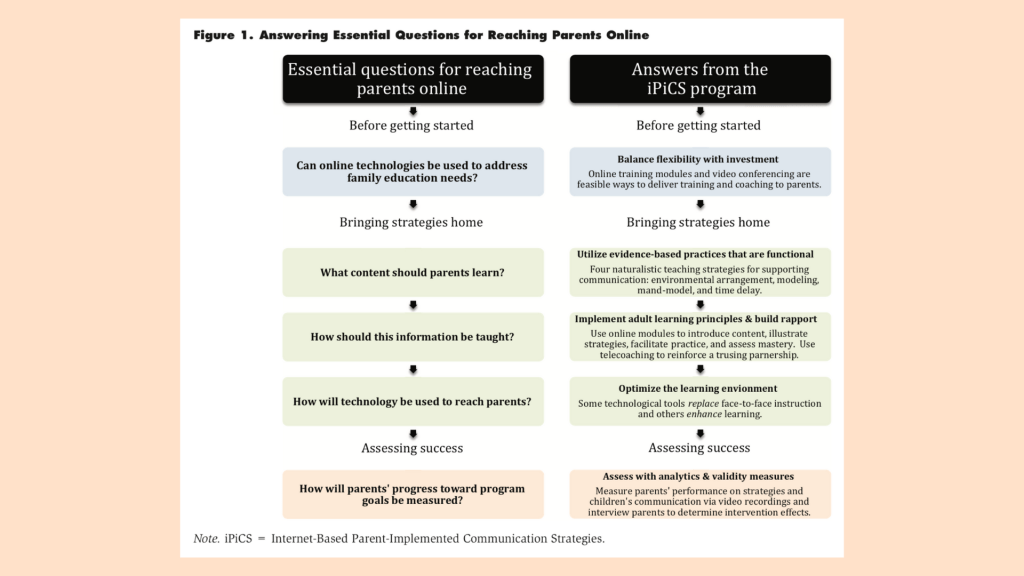

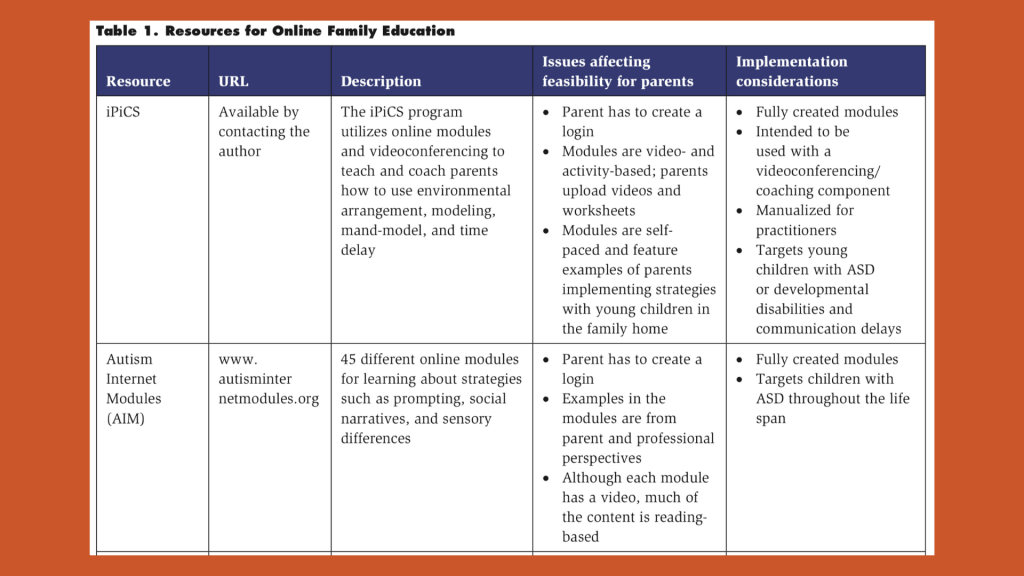

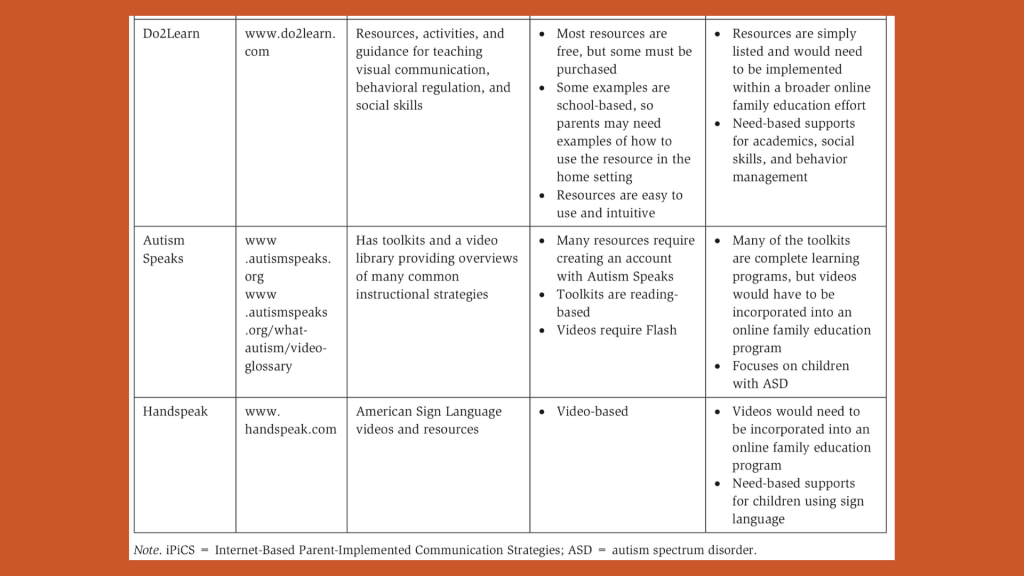

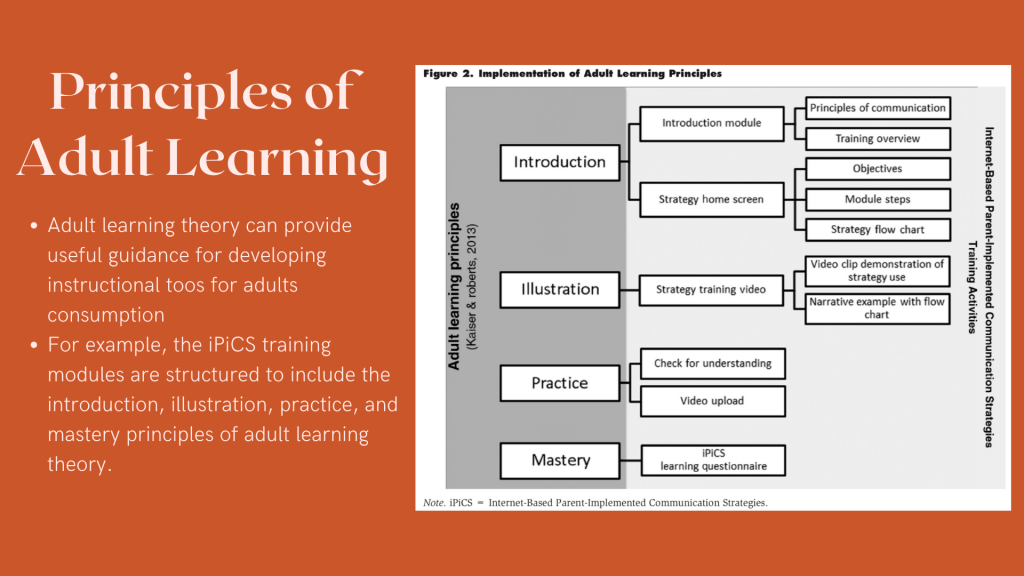

Bringing Instructional Strategies Home: Reaching Families Online

Curtiss, S.L., Pearson, J.N., Akamoglu, Y., Wolowiet-Fisher, K., Snodgrass, M.R., Meyer, L.E., Meadan, H., & Halle, J.W. (2016). Bringing instructional strategies home: Researching families online. Teaching Exceptional Children, 48(3), 159 – 167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0040059915605816

Contact us for access to this article, or check out the summary below.

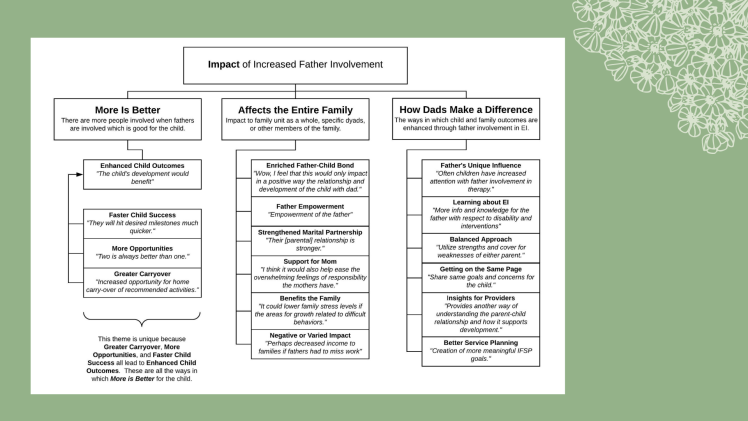

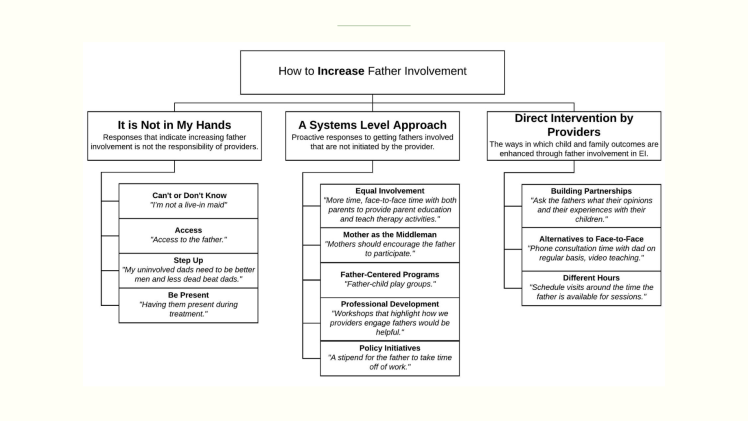

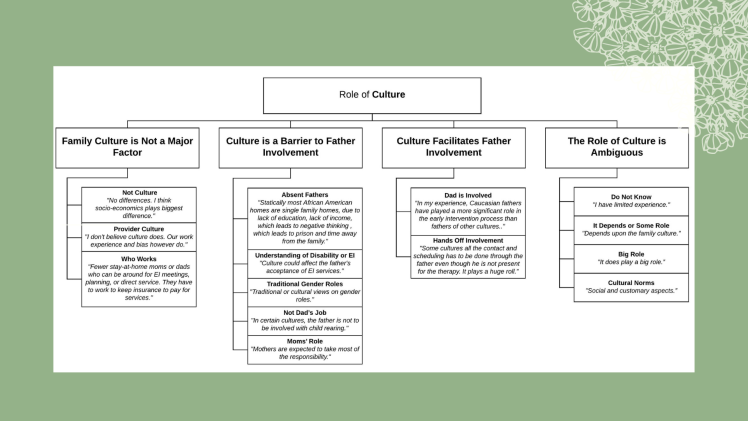

Understanding Provider Attitudes Regarding Father Involvement in Early Intervention

Curtiss, S.L., McBride, B.A., Uchima, K.,Laxman, D. J., Santos, R. M., Weglarz-Ward, J., & Kern, J. (2021). Understanding provider perspectives: Father involvement in early intervention. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 41(2), 147–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121419844829

A preprint of the whole article is free, and the summary is below.

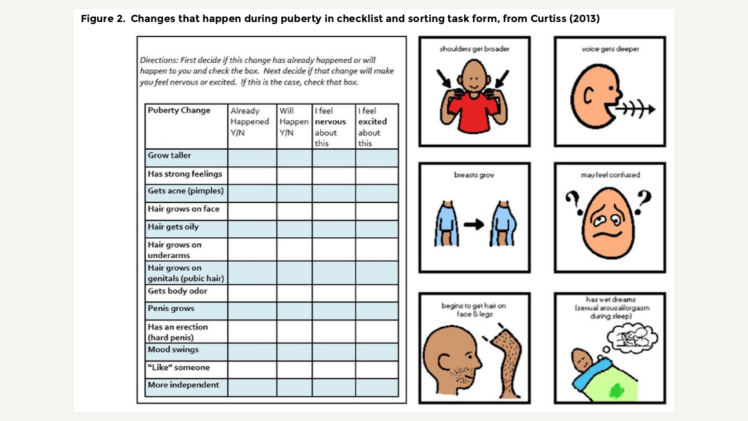

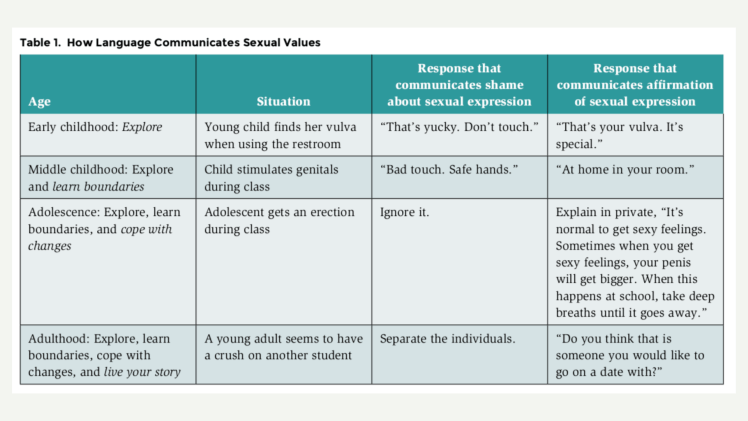

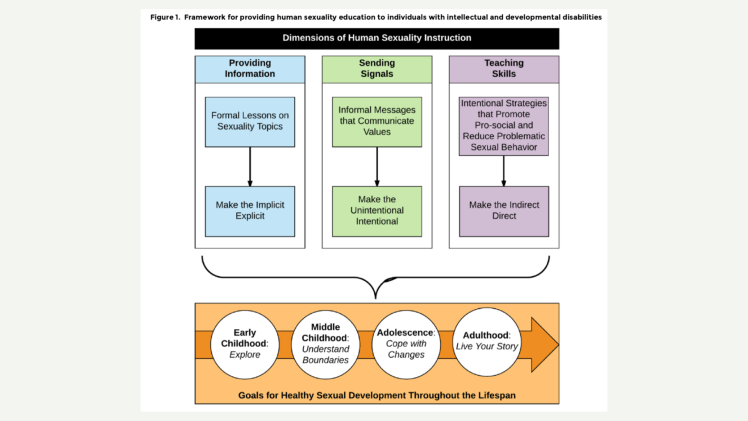

The Birds and the Bees: Teaching Comprehensive Human Sexuality Education

Curtiss, S.L. (2018). The birds and the bees: Teaching comprehensive human sexuality education. Teaching Exceptional Children, 51(2), 134-143. https://doi.org/10.1177/0040059918794029

A preprint of the whole article is free, and the summary is below.

Building Capacity to Deliver Sex Education to Individuals with Autism

Curtiss, S.L., & Ebata, A.T. (2016). Building capacity to deliver sex education to individuals with autism. Sexuality and Disability, 34, 27-47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-016-9429-9

A preprint of the whole article is available for free.

![The language used to express sexual information is often vague and relies on implicit deductions... [this] makes learning about human sexuality difficult for all students but especially those with IDD.](https://autismincontext.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/8-2.png?w=750)